Legfrissebb kiadás

|

Falevelek a szélben Magvető kiadó, 2017 |

hand crank height adjustable desk

"I’ve been a Jewish Hungarian or a Hungarian Jew at various stages of my life. Today, I am a Jew when I hear that the Jews are mean and pushy. And I am a Hungarian when people say that the Hungarians are fascists."

Survivors of the 1944-45 Budapest Holocaust of Jews still recall with incredulity their own matter-of-fact childhood acceptance of the constant danger of random, casual death. A girl in a landmark new autobiography stands by the icy River Danube with a group of adults led there by a Nazi Arrow Cross death-squad for execution. All of them die under fire, except the child because the machine-gunner runs out of ammunition. He growls: “Get back and be a good girl.” She returns home and tells her cousin, the narrator: “I saw Aunt Sarah killed. Don’t tell mummy, she might get upset.”

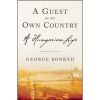

This scene is from A Guest in My Own Country: A Hungarian Life (Other Press, 2007) by George Konrad (György Konrád), a best-selling novelist and literary legend. The book published in America has won this year’s National Jewish Book Award there in the category of Biography, Autobiography and Memoir.

Konrád has also just published a spicy collection of pithy and often startling essays, recollections and reflections on life spent under tyranny, mostly alone and almost always in danger. Inevitable English, German and French translations of this Hungarian first edition Inga (Pendulum; Noran, Budapest, 2008) may well crown his career.

I met the author at his home in the gentle Buda hills days before Hungary’s recent National Independence Day celebrations that brought Neo-Nazi thugs on to the streets in violent demonstrations quelled only by tear-gas grenades and the threat of water cannon. Several activists managed to set each other on fire when they mishandled Molotov cocktails prepared against the riot police. Some residents in old Pest, usually a very civilized lot, pelted them with rubbish from the upper floors of their long-neglected, elegant Neo-Baroque and Art-Deco apartment blocks. They were irritated by the presence in the crowd of members of the recently formed Hungarian Guard modelled on the bygone, indigenous Arrow Cross Party that had assisted the occupying German forces in the murder of Jews during the Holocaust.

“I’ve been a Jewish Hungarian or a Hungarian Jew at various stages of my life,” Konrád opened the interview. “Today, I am a Jew when I hear that the Jews are mean and pushy. And I am a Hungarian when people say that the Hungarians are fascists.

“I love Budapest with its many moods and faces,” he went on, “even despite its present gloom and nervousness. I nowadays consume fewer words and fewer people than I used to. I best enjoy life when I retreat to my study either here or in my house in the country. Occasionally I still venture abroad, but mostly I spend my time delighting in my family and friends. I have grown into an older man still just managing to work while my health and mind still just function.”

That is probably an exaggeration. Konrád is a sprightly 75-year-old fired with boundless curiosity, still reluctantly participating in relentless political debate and maintaining a steady, robust literary output. The interview was tactfully managed by the author Judit Lakner, his radiant wife decades his junior. It had been arranged with help by their enchanting early-teenage daughter and it ended when my host had to rush off to address a party of authors and readers.

Konrád has taken a leading role in Hungary’s turbulent return to democratic rule since the implosion of communist power two decades ago. He is the only Hungarian author to have virtually all his writing profitably published in excellent translations in the West. He is regarded by his readers worldwide as a dissident East European writer par excellence. He is a former president of International PEN (1990–1993) and the Berlin Academy of Arts (1997–2003). His fame has elevated him to a place among the great and good of literature courted by the establishment with coveted honours, including the Ordre National de la Légion d’honneur, the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade and the International Charlemagne Prize of Aachen. Most recently, he received the prestigious Franz Werfel Human Rights Award, and before that an honorary doctorate from the University of Novi Sad, probably a reward for his widely publicized plea against Nato bombing during the Balkan wars.

This is how Hans-Henning Paetzke, Konrád’s German translator, describes the author: “At first sight, Konrád manages to conceal his constant creative tension, his voracious appetite for the whirl of the great metropolis and the very different bustle of the small Central European village where he soaks up the tales of his fellows’ lives. He is a spy of the soul, a thief of yarns and anecdotes, a sociologist, a non-conformist anti-politician, an Eastern sage and an Old Testament prophet, a true man and a true novelist giving account of innumerable lives including his own. He eschews a hint of didactic moral superiority even as he depicts the killers he had to stare down at age 11. He deploys, instead, his indispensable, delicate irony.”

The book A Guest in My Own Country comprises two interrelated pieces. The first is “Up on the Hill at the Solar Eclipse” (originally published in Hungarian in 2003), describing the author’s personal experience of the rise and fall of Communism in Central Europe and the intermittent current transition to liberal democracy. It is a sequel to the second part, “Going Away and Coming Home” (2002), a child’s view of the slaughter in wartime Budapest, one of the finest works of all Holocaust literature.

This relates how the author fortuitously sought shelter as a child with his older sister in the troubled capital just one day before all the Jews in the children’s provincial hometown of Berettyóújfalu were deported to the Nazi death camps. The subsequent piece of autobiography opens with a tidy moral dilemma facing a boy imbued with a love of his homeland about the meaning of patriotic loyalty to a nation that has betrayed him.

The combined English-language edition, ably translated by Jim Tucker and edited by Michael Henry Heim, explores an essential, bloody chapter of European history still beyond the comprehension of most people outside this region. Pendulum is a synthesis of life under tyranny. He writes:

Autobiography?... I was six years old when the Second World War broke out, 11 when a combination of good luck and good sense spared my life and 12 when I survived National Socialism. At 15, I witnessed the energetic introduction of Communism, I have aged along with it and had passed 56 when at last it expired... All major circumstances in my life have come about from my adolescent decision to become a writer.

That decision was a child’s response to racist terror, the provocative symbols of which have now returned to public life in Budapest. How does he respond now to the march of another paramilitary racist organization on the streets of his beloved Budapest? The writer reflects: “I have not yet had a personal encounter with the present bunch. There are many such organizations in Western democracies. In Hungary, they are effectively illegal because here the state holds a constitutional monopoly over military organization. And this is at last being recognized by the authorities. But in other countries, where citizens have a right to bear arms, such as the United States, militaristic organizations regularly train their members in armed combat. They also preach a creed of white supremacy and religious intolerance. I happened to be in the USA at the time of the Oklahoma bombing in April 1995. But the USA is such a huge country, and its freedom of expression is so securely founded that expressions of rightist fanatic dissent over there are not as alarming as they are to us here in Central Europe. The Ku Klux Klan has not invaded American public life. Yet things are basically similar in Hungary, not least because we are now part of the European Union. Segments of the Hungarian elite may be pleased by the emergence of the Hungarian Guard, but they will never admit that in public. They might like to use the Far Right for their near-term purposes but would not wish to be publicly associated with it because that would injure the country’s long-term interests. And the Hungarian elite is committed to its own interests rooted in Hungary’s economic success.”

An alternative development model is offered by Russia, “an autocratic, pseudo-democratic state,” Konrád thinks, “like Hungary used to be before the Second World War. But would any significant part of Hungarian society ever look to Moscow for political direction and an opportunity for integration? No way. Besides which, there is Ukraine between us, a very large country. This country therefore must look for various sources of support from the West, which insists on respect for the rule of law. Europeans tend to look westward anyway. Look how the west end of every city is always more prosperous than its east end. The Jews too have always settled in the east end everywhere, as they had come from the East, and then re-settled in the west end the moment they became successful.”

I asked Konrád how he explained the phenomenon of nationalists in the Guard marching to tunes celebrating a discredited Hungarian government that had served the interests of a foreign power. “People often show greater sympathy to their grandparents than to their parents,” he ventures. “Children know when their parents are guilty of something, and they like to disassociate themselves from that. But they try to understand and forgive their grandparents. In Hungary, it was the grandparents’ generation that was smeared by Nazi deeds and sentiments. The parents’ generation was associated with Communism. It is the grandchildren’s generation that feels today that its forebears have been unjustly treated. And there are lots of youngsters in every society who like to march and sing and train with dummy rifles. The Hungarian Guard must be full of them. Are they likely to become real Arrow Cross bands? They might, perhaps, if there were a Hitler in Germany to lead them. Would they target the Jews? No, I think nowadays they Hand Crank Height Adjustable Desk would more likely persecute the defenceless Hungarian Gypsies. But as they would not gain much by robbing the destitute Gypsy communities, I think they would only show them cruelty. If they had a chance.”

Thomas Ország-Land

Thomas Ország-Land